Philippine Crocodile

Description

The Philippine crocodile is one of the most endangered freshwater crocodiles. It is small with a relatively broad snout and thick bony plates on its back. Until recently, the Philippine crocodile was considered a subspecies of the very similar New Guinea crocodile (Crocodylus novaguineae).

Biology

Philippine crocodiles are thought to feed mainly on fish, invertebrates and small amphibians and reptiles but very little else is known about the natural history or ecology of wild populations. In captivity, females build mound-nests at the end of the dry season from leaf litter and mud, upon which they lay a relatively small clutch of 7 – 14 eggs. Females show parental care of both the eggs and hatchlings.

Threats

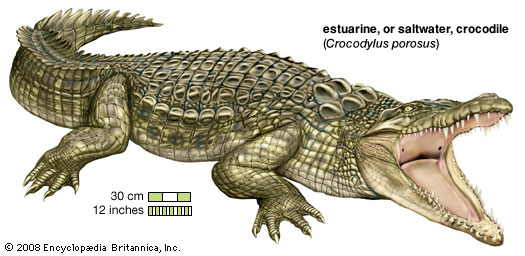

The massive population decline of the Philippine crocodile was originally caused by excessive over-exploitation for commercial use (2). Today, habitat destruction is the most pressing threat to species survival, with rain forests being cleared throughout the region to make way for rice fields in an effort to cope with the human population explosion (2). Locals in this area are also in contact with the infamous esturine or ‘saltwater’ crocodile (Crocodylus porosus), which is one of the largest reptiles in the world and has a reputation as a man-eater. This factor undoubtedly contributes to local intolerance of any crocodile species, even the small Philippine crocodile, which is often killed when encountered (5). The very word for ‘crocodile’ in the Filipino language is a vile insult.

Conservation

Next to the Chinese alligator (Alligator sinensis), the Philippine crocodile is considered to be the most endangered crocodilian in the world. Some authorities believe there may be less than 100 individuals left in the wild , although some wild habitat still remains. Urgent research is needed to assess the current status, in order to implement an effective management strategy for this remaining wild population. This species is protected from international trade by its listing on Appendix I of the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species (CITES), but there is only one officially protected area within the Philippines, and this is poorly enforced. At present, captive breeding takes place in a small programe run by the Silliman University and at the government-run Crocodile Farming Institute, which breeds crocodiles for commercial and conservation reasons. Sadly, there is currently little political will or local tolerance to save this ancient reptile in the wild and for the short term at least, captive breeding programs may be the key to the, at least nominal, survival of this crocodile.

Recommended Posts

Why native trees?

February 07, 2018

Visayan Warty Pig Wild Swine with a WILD Look

January 06, 2018