National Catholic Reporter’s Global Sisters’ Report

Safer and climate-resilient communities

Recently, I took six graduate students in Climate Change and Disaster Risk Reduction Management (DRRM) from the Philippine Women University (PWU) for a site visit to Payatas, Quezon City, an urban resettlement area. I have gone to the area before and trained some of the groups there in environmental leadership, but this time being with the students, it turned out to be a very different kind of engagement.

Payatas is one of the most densely populated areas in Manila where the incidence of poverty is quite high. It is also the site of the controversial and biggest garbage dump serving various cities in metro Manila. According to Professor Ebinezer Florano, the Payatas area has served as an open dumpsite for metro Manila since the 1970s, accepting a record 3,000 tons of solid waste daily in 1993. The dumpsite has been ordered to be closed repeatedly under the Ecological Solid Waste Act (RA 9003), however, it continues to remain open. Garbage scavengers form the informal waste sector and continue to make their livelihood there.

All six women students are candidates for the Masters of Science in Environmental Management of the Philippine Women University. We went to Payatas to learn about the community based disaster risk reduction management (CDRRM), a program implemented by a grassroots organization who call themselves UMAKAP (Ugnayan ng Mamamayan Para sa Kaunlaran ng Payatas.Translation: Citizens Movement for Payatas Development). It is composed mostly of women and a few men who participated in the disaster and risk management training for two years.

According to history, Payatas had several disasters; the most severe happened on July 10, 2000, where a portion of the dumpsite caved in. The massive landslide of 50 feet of solid waste was caused by continuous rain brought on by two consecutive high category typhoons — Kirogi and Kai-tak (locally named Ditang and Edeng, respectively). The landslide, specially termed, “trash-slide” by locals, covered several shanties at the foot of the dumpsite and claimed an undetermined number of lives. According to reports, at least 300 adults and children had been buried under a mountain of waste. This event became a national embarrassment for the Philippines as a country where most of the population lives in destitute poverty.

The government, church and civil society organizations have been partnering to help this community, including the Simbahang Lingkod ng Bayan (SLB), a social advocacy group of the Philippine Jesuits. I am a climate change adaptation consultant for SLB, which has been training the group and its members in community-based disaster risk reduction since 2014.

The women shared their experience of floods, fires and “trash slides” — and their daunting anxiety over a methane explosion from a mountain of garbage which is continuously increasing in volume, even though the dumpsite was ordered to be closed about two years ago. UMAKAP members think that the increase in volume is because of the planned expansion of current “waste-to-energy” project operating in the dumpsite.

The women from the community took our group to visit the area next to the garbage mountain. The students were stunned at the situation they witnessed. Three of the students who are government employees of the Environment Management Bureau were upset. As it turned out, we could not walk further to get near the garbage mountain and the creek to check the area that UMAKAP members complain has a discharge with black leachate. Two men in yellow shirts guarding the garbage dump area stopped us and warned not to take photos. There was an eerie feeling of fear among us and the UMAKAP women. During the debriefing, one of the students suggested that the issue must be reported to the Department of Environment for an environment audit.

The women have learned a lot from previous disasters in the dumpsite, and these experiences made them prioritize training in disaster risk mitigation and management. They partnered with SLB to do capacity training in community-based disaster-risk reduction training. For two years they have been working on this and have developed their disaster-risk reduction manual and emergency procedures.

The group not only succeeded in disaster- and risk-reduction management but also addressed the poverty and lack of livelihood of the community. The women have established a small store that sells rice and gives credit to the members on a trust basis. Acknowledging the importance of alternative medicine during disasters, the group initiated an organic herbal and medicinal garden. First aid medication will be readily available during times of disaster. They have plans to develop organic vegetable gardens to alleviate incidences of hunger.

I have been inspired by how these women are leading in the fight for their communities’ future in a climate-changing world. Women and local communities are the key to mitigating disasters and the key to the success in community based disaster risk reduction programs. They are prime movers in ecosystem rehabilitation and environment conservation.

Back in the classroom, I asked the students to write a reflective report on the Payatas visit. Some of them mentioned that visiting Payatas opened their eyes to the importance of their studies and how in the future they can help build sustainable communities. They also found out that political will is needed to address Payatas’ problem and that local communities have the power to choose a healthy environment for themselves.

Meanwhile, the women of Payatas continue to fight the corporate greed of those behind the Payatas landfill, exposing the environmental dangers by sharing their stories and not being afraid to tell the horror of how these corporations and local leaders profit from waste instead of reducing it. Their fear is not enough to silence them to fight for their environment.

As Pope Francis calls for all Catholics and Christians to exercise their work of goodness and mercy by protecting the environment, the story of the women and men in Payatas serves as an example of how in our daily lives we can fight for a clean and safer environment.

[Maryknoll Sr. Marvie Misolas is currently serving in the Philippines after mission work in Taiwan for many years. She studied Environment and Peace at the University for Peace in Costa Rica, specializing on Climate Change and related issues. She is now based in Manila where she teaches, works with climate vulnerable communities and advocates for the care of the environment in collaboration with other environmental networks.]

Recommended Posts

Energy Transition and the Transport Sector

March 15, 2024

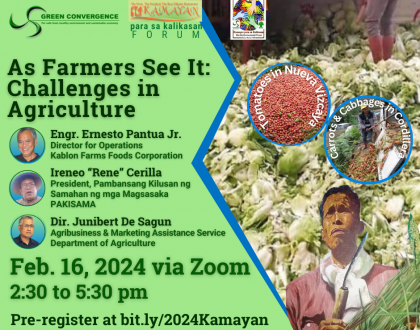

As Farmers See It: Challenges in Agriculture

February 16, 2024